The Legend of Crazy Horse

Dispatch XV

A Vagabond Adventure

Continent # 1: North America

The Origin of Crazy Horse

Day 50 - November 14, 2021

In the summer of 1857 a light skinned, 17-year-old Oglala Sioux brave whose mother nicknamed Curly, decided to go on a vision quest so that he could understand the future path his life should take. His father, sometimes known as Worm, was a respected shaman in the tribe. He made arrangements and accompanied his son on his quest so that he did it the proper Sioux way. They rode away, fasted and set up a sweat lodge where they spent time and discussed his future. In Curly’s dream he saw a plain horseman. He was not painted, and he told Curly to never adorn himself either. He was to wear no war bonnets, only a single feather, if that, and a small stone behind his ear. In battle he was told no arrows or bullets could hurt him; only a member of his own people could do him harm. And he was never to keep anything for himself, but to do his best to take care of the poor and helpless in his tribe and be a man of charity.

The boy would later take the name Crazy Horse — Tȟašúŋke Witkó to his people — literally, “his-Horse-Is-Crazy.” And for most of his life, he lived his vision quest. He took care of his people, and kept nothing for himself and during the final ten years of his short life was a good and strong leader. Yet he was an unusual man, even among his own people. Early in life before he became a famous warrior, he would often ride off without warning and disappear without explanation into the plains of what are now South Dakota, Nebraska, Utah and Montana for weeks. He was quick witted, but quiet and never sang or danced, even though the Lakota liked to do both.

Other native American leaders — Spotted Tail, Little Big Man, Red Cloud — eventually saw that fighting the hoards of people coming from the east was futile. But Crazy Horse could not accept this truth. He loved the land he grew up in, and perhaps that is why, along with Sitting Bull, he never accepted that his people should bend to the will of the white race that was changing his world so rapidly.

A sketch of Crazy Horse made in 1934 by a Mormon missionary after interviewing Crazy Horse's sister, according to PBS’s TV show History Detectives. His sister agreed the depiction was accurate. No photo was ever taken of him.

Visiting Crazy Horse Memorial

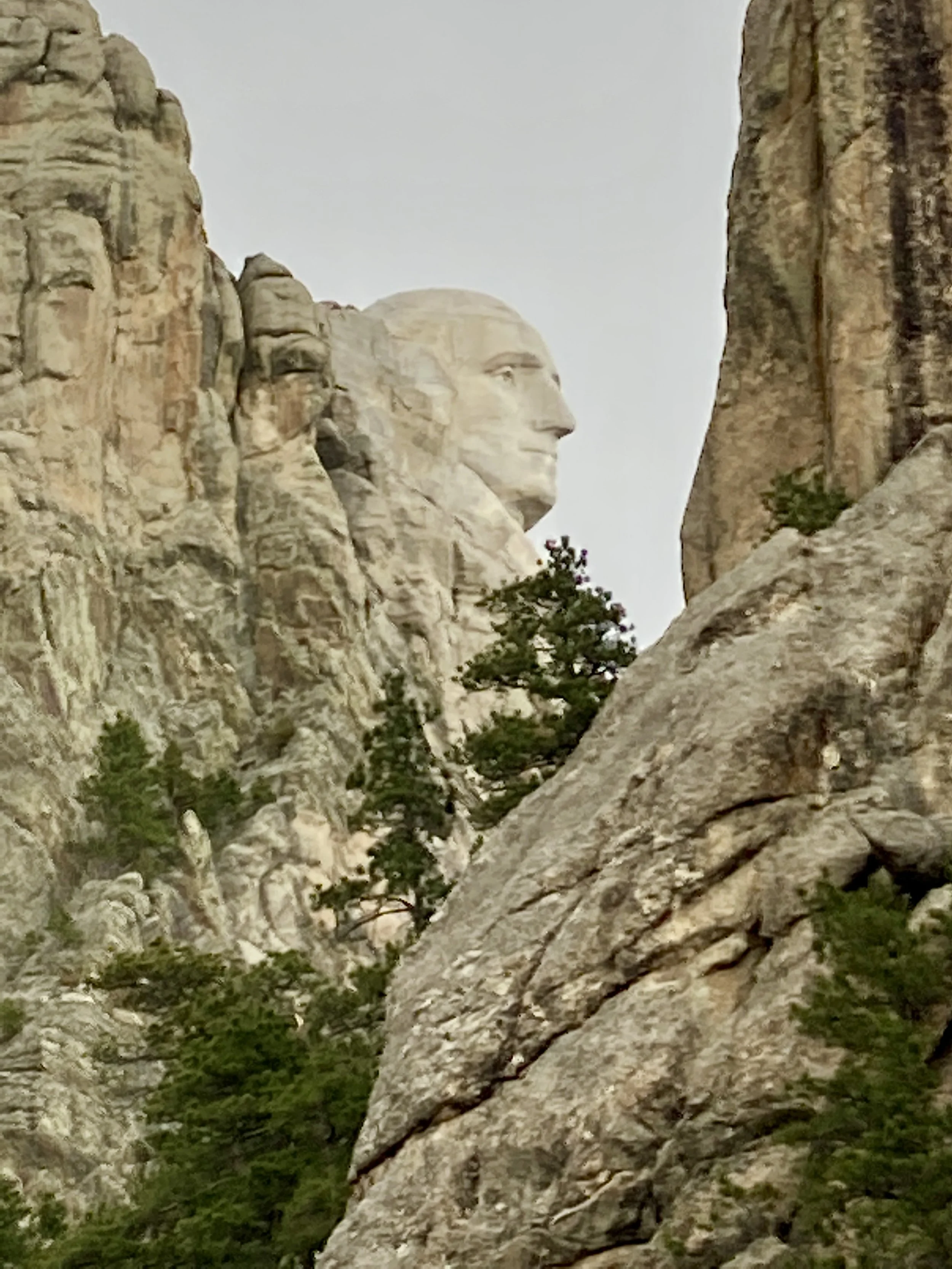

The weather was perfect the day we headed out of Mt. Rushmore through its spectacular granite mountains and tall stands of pine to find the Crazy Horse Memorial. I snapped one last picture of George Washington on the way past the presidents. I had been told it was a unique view of the first president.

We bid farewell to George Washington and Mount Rushmore’s presidents, but snapped this unusual view of the first president as we drove away. (Photo - Chip Walter)

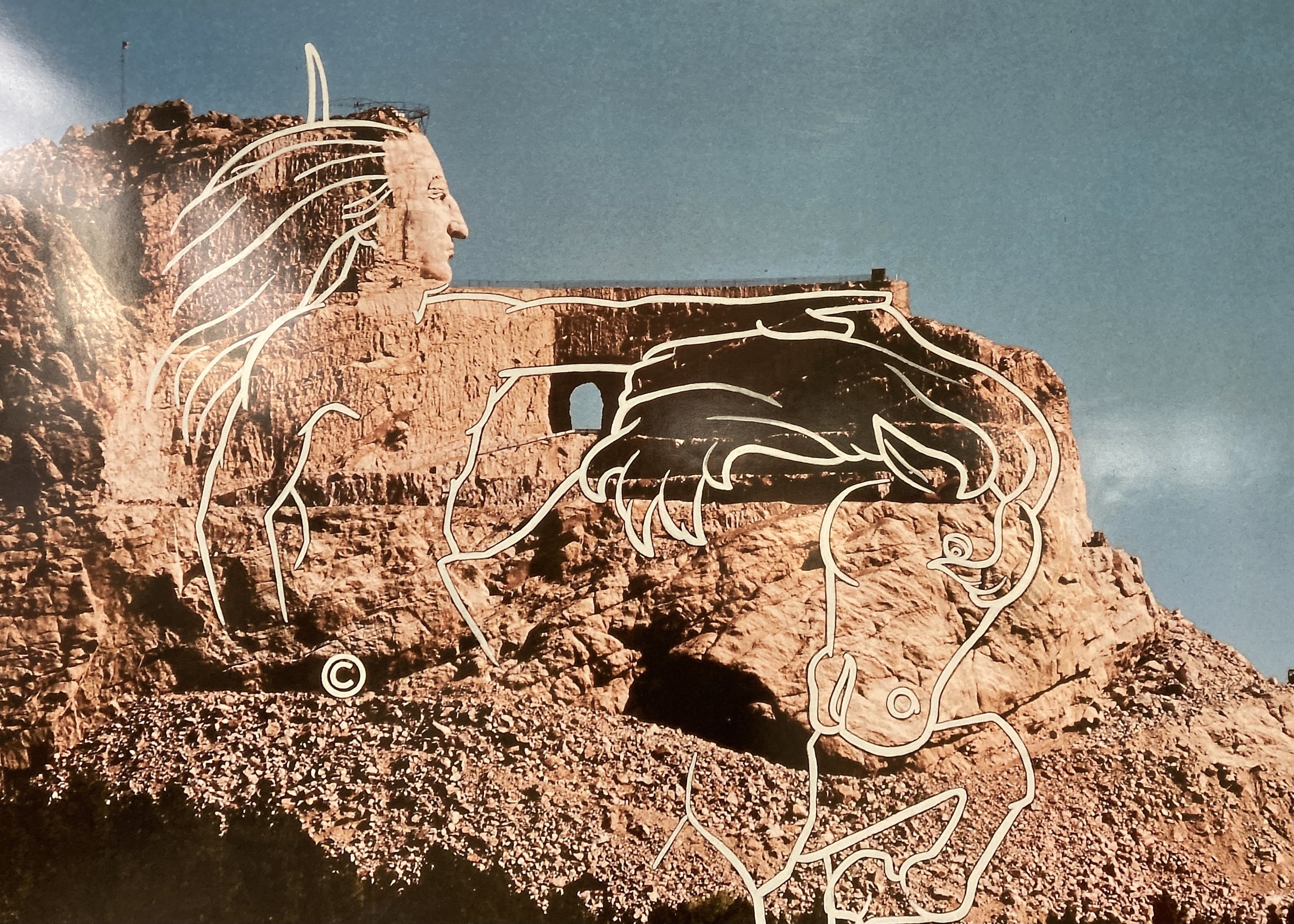

We were switch-backing our way toward Custer, SD, ironically the closest town to the great Sioux warrior’s memorial, when black clouds suddenly swept by and obliterated the morning’s chromium blue sky. Ferocious winds kicked up, and during our 30 minute drive, the temperature dropped from 60 degrees to 30. Hard and angry flakes of snow whipped by, but I stopped noticing them once we caught a glimpse of Thunderhead Mountain and the immense sculpture that was emerging from the rock — Crazy Horse racing into the wind, his immense left arm reaching forward.

The Emerging Image of the Crazy Horse Sculpture. (If you look closely you can see the outline of his horse’s head below on the right.) (Photo Chip Walter)

In 1872, when the sacred Black Hills that had been guaranteed to native Americans under treaty in 1868 were taken back because of the gold that had been found there (desperately desired in Washington DC following what became known as the economic panic of 1873), Crazy Horse refused to give in. He fought blue coat battles from 1866 to 1876, including the most famous one of all, Little Big Horn. There the Sioux, with Crazy Horse as one of their leaders, wiped out General George Armstrong Custer’s 7th Cavalry after native Americans were attacked while camping at a bend in the Little Big Horn river. The Sioux had not planned a battle, but counter-attacked and won with overwhelming numbers and superior strategy. Custer died near a ridge a mile away from the river, surrounded by his men. Most military experts agree Custer refused to see that his entire force was overmatched. Even his scouts counseled against attacking. (More on this in another Dispatch when we visit the place where Custer and his men died.)

A New Monument. Building the Crazy Horse Memorial.

On November 7, 1939, a Boston sculptor named Korczak Ziółkowski was contacted by native American Lakota Chief Henry Standing Bear. The chief knew Ziółkowski had worked under Gutzon Borglum on Mount Rushmore, and he admired previous works that the sculptor had done. Would Ziółkowski be interested in creating a monument for native Americans. "My fellow chiefs and I would like the white man to know the red man has great heroes, too,” he wrote. Thunderhead Mountain, between the town of Custer and Mt Rushmore, was the sight they had in mind.

While Rushmore is reasonably complete, Crazy Horse has a long way to go. Funding has always been a challenge. From the beginning Ziółkowski insisted the monument pay for itself. And it does, mostly with the $25 we and millions of other visitors pay when they enter the memorial. The project has never been subsidized with federal money.

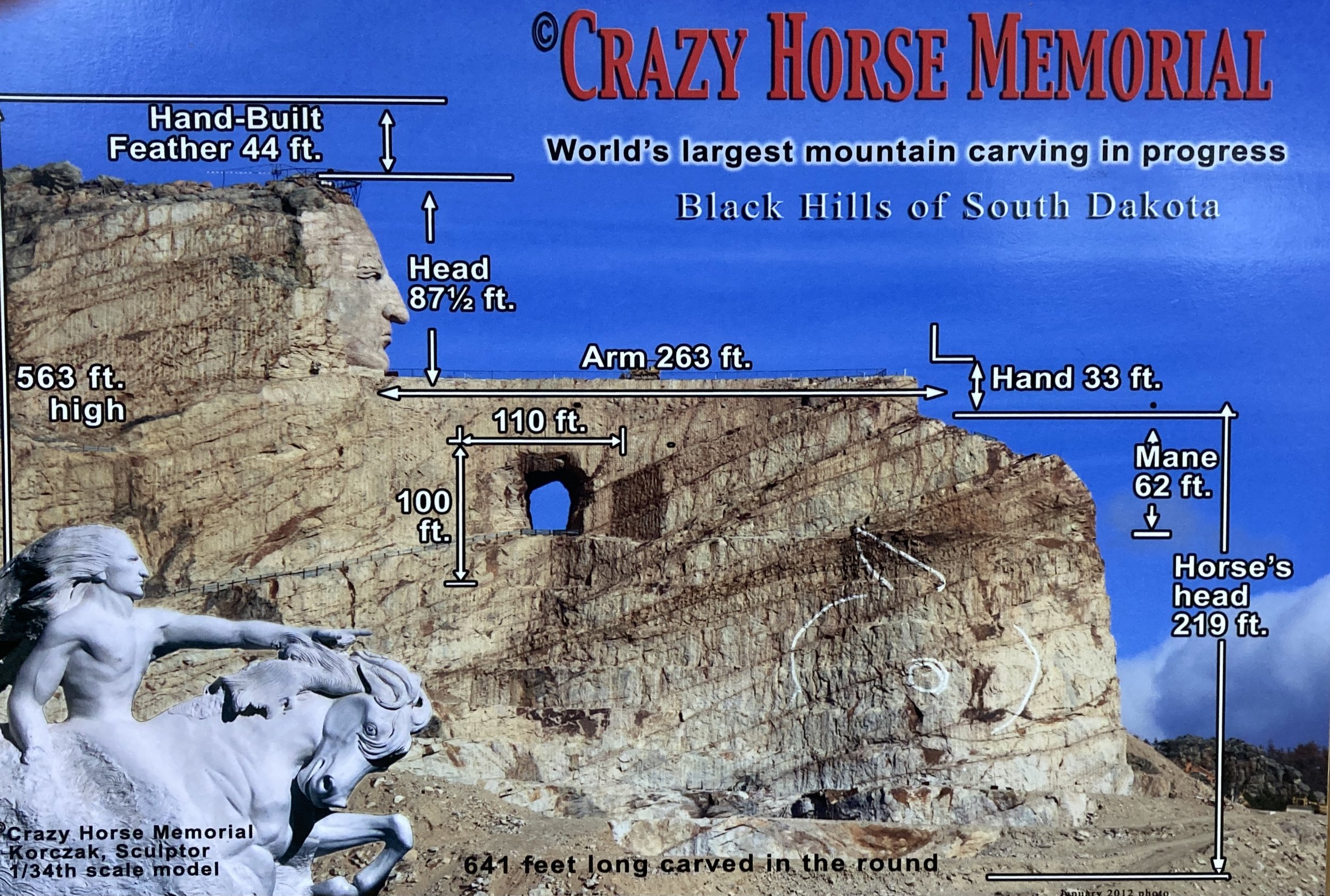

More than funding, the shear size of the monument explains why so much remains to be done, even after hundreds of tons of rock have been blasted away. When completed the sculpture will be the world’s largest; bigger than Mount Rushmore, taller than the Great Sphinx of Giza and the Statue of the Liberty, broader than the Tang Dynasty Buddha of China. In the end it will be 641 feet long and 563 feet high.

A 1/300th scale model of the sculpture created by Korczak Ziółkowski. (Photo Chip Walter) Below two pictures provided by the Crazy Horse Memorial illustrate the sculpture’s colossal dimensions and an idea of what the final version will look like.

Today the grandchildren of Ziółkowski and his wife Ruth Ross, still work with the Sioux people to manage what has grown to a sprawling and beautiful monument to native nations. It features the Indian Museum of North America, and Native American Cultural Center, restaurants, shops and a planned satellite campus of the University of South Dakota. Cyndy and I walked through the center, viewed the rich and beautiful artwork and photographs, and were inspired.

Crazy Horse died in the summer of 1877, bayoneted by a soldier at Fort Robinson after he and his band of followers, starving and in poor health, turned themselves into the federal government.

From the Library of Congress - a drawing by Mr. Hottes as Crazy Horse and his Oglala followers head to surrender to General Crook at Red Cloud Agency May 6, 1877. Crazy Horse died 4 months later.

He was attempting to escape while being sent to jail according to those who witnessed his death. He passed away that night at the age of 37, laying on the ground because he refused to be put in a white man’s bed.

We prepared for the next leg of our journey: Deadwood, Calamity, Jane, Custer State Park, and Wild Bill Hickok. Within eyesight we could see the great mountain and the face of Crazy Horse, 87 feet high, his riveted eyes 17 feet wide; all of him, and his crazy horse, waiting to emerge from the rock. I thought of his quote when a white man asked Carzy Horse, “Where are your lands now?”

“My lands,” he answered, “are where my dead lie buried.”

This is a series about a Vagabond Adventure - author and National Geographic Explorer Chip Walter and his wife Cyndy’s personal journey to explore all seven continents, all seven seas and 100+ countries, never traveling by jet.

——————————————————————————————————————

As of this Dispatch …

We have travelled 4650 miles, across four ferries, on five trains, visiting three World Heritage Sites, through 13 states, three National Parks and memorials, and three Canadian provinces, in 26 different beds, and seen more different kinds of hotel keys than there are prairie dogs on South Dakota’s Badlands.