Driving Mexico’s Baja 1000 - Part One

Dispatch XXIV

A Vagabond’s Adventure - Continent # 1: North America

Baja California

January 24, 2022 - San Diego to Tijuana - Days 90 to 92

Another perfect San Diego morning. From Mission Beach we hop Lyft to the Mexican border. There Cyn and I climb out of the car and stand like a couple of waifs on the street corner and struggle to get our bearings. We find a sign: Border Crossing and follow with bags on our backs to revolving metal doors. Above us the simple massive word: MEXICO.

Beyond the doors we pass through a dark, vaguely sinister feeling hallway. Had I seen too many movies about nasty border guards in Spanish speaking countries? Arrive at a counter with plexiglass windows. Very standard. The moment we open our gringo mouths a slim, crisply dressed uniformed border guard pulls us aside, and sits us in a room nearby. Oh-oh.

“Where are you from?” He asks in perfect English.

A couple of gringos enter Mexico. (Photo Chip Walter)

We tell him. He kindly requests our passports. We hand them over, answer a few other perfunctory questions, pay a fee of $35 each (was that really necessary?) and are quickly freed to snake along a second labyrinth that brings us into suddenly blinding sunlight and a Mexican sidewalk swimming with taxi drivers. We need one to reach Oui Madame, the Bed and Breakfast where a generous friend is providing us with a car so we can drive the 1000 miles from Tijuana to San Jose del Cabo. A bit of dickering on the price and then we rattle off in a battered Tijuana Taxi.

The road swings us toward the coast and to the left a long metal wall, 30 feet high that seals America and Mexico from one another reveals itself. It looks formidable, but I knew from work I had done in the past that there were many places south of San Diego where immigrants braved the open valleys between Tijuana and San Diego. After my days at CNN bureau, Tim Sevison, a former CNN cameraman, and I created a video production company and shot segments for various cable outlets including stories about these daily attempts to make it to the United States.

I remember watching as each sunset, hopeful immigrants crowded by the high and broken cyclone fences in Mexico to await the darkness. Meanwhile, in San Diego, the border patrols agents steeled themselves for a race to find them as they scrambled into the no man’s land between the two nations. It was like this every night and every night the border patrol agents would round up as many hopefuls as possible, while scores of other immigrants made it into the US to begin a new life. That was the 1980s. It seems not much has changed since then, although it appears the cyclone fences had been replaced with more formidable barriers.

Tijuana to El Rosario

At Oui Madame we met Dominik, the diminutive and amiable owner of his B&B. Dominik grew up in Montreal (thus the French name of the B&B) and had been living in Tijuana for 12 years. Now he was about to sell the place to buy property in the forests north of Puerto Vallarta.

“Why?” I ask.

He shrugs, “It’s just time to get away.”

We walk out to the car. I wasn’t sure what to expect but it wasn’t the sweet Mercedes SUV, vintage 2014 that awaited. A car this rugged was more than we could have hoped for! Much like a good rental agent, Dominik explains a few of the car’s peccadilloes, and we pile our baggage inside.

“Now, before you leave,” Dominik says, “Don’t travel after dark.” This isn’t because any banditos will run us down, he explains, but because Mexico’s Highway 1 doesn’t have all of the reflectors and barriers we might be used to. “You could just go straight when you should have turned and launch yourself into the night,“ he smiles. "Also, cows often cross the roads and unlike deer (and much like moose), you can’t see the reflection in their eyes. “You don’t want any head on collisions.”

It’s late morning so I ask where the next town is that we can reach before dark.

“El Rosario,” he says. “And the day after that, Guerrero Negro and then you’ll cross over from the west to the east of the peninsula through desert where you want to get to Mulege. You should find a place to stay there.

With our marching orders and a wave, Dominik sends us off. We roll south, iPhone GPS in hand, but not before filling the tank and making for a Santander Bank to pick up a few pesos. At the bank’s ATM the line is long. It’s Monday and I guess that it’s pay day. Later I would notice that we saw this a lot throughout Mexico. Payday means cash and, at least so far, it seems cash, not credit and debit cards, is king.

I extract some cash and promptly leave my debit card in the machine. Once I get to the car it hits me. Panicked, I sprint across the parking lot, only to find the security guard walking toward me with a grin as he hands me my card. I pump his hand so hard I think he fears I’ll pull it off. This was an omen. We have nothing to fear in Mexico. In fact from the time we cross the border we never meet a single surly person anywhere in the country.

In Tijuana nearly everything is battered – the cars, the roads, buildings. But the battering has a certain beauty about it. Small islands of green poke out here and there along the urban roadside. The stores we pass are mostly one story, colorful and busy. Soon we hit Highway 1 and follow the signs to Ensenada. In an hour we are making our way into town where the highway sweeps us above a broad, splendid bay. In town on the right are beaches and hotels, on the left a maintenance road and rows of gas stations, shack restaurants, car repair shops, bodegas and mercados.

We grab a bite to eat in a restaurant that overhangs gargantuan igneous rocks as the Pacific Ocean crashes dramatically before us. The ceviche is delicious, but it’s time to get moving because we need to make El Rosario before dark.

Coming into Ensenada Bay, Mexico (Photo Chip Walter)

Outside of Ensenada rolling hills take us away from the coast and into miles of vineyards. This is the wine country of Mexico. The landscape is green and fertile. The valleys between low mountains by the sea make for very happy grapes. Growing grapes in Mexico goes back to the 16th century when the Spanish arrived, and today this area just south of Ensenada is where most of the grapes are because they are just north of the 30th latitude. It’s still a fledgling business with all sorts of mash-up wines: French, Spanish, and Italian grapes, from Nebbiolo to Chenin Blanc. Mexico likes to blend its wines even if they don’t follow European traditions.

Beyond the vineyards and seemingly out of nowhere we run into a wall of traffic. Highway 1 has taken us right into the heart of the city of San Quintin, and we wait, painfully moving past miles of more shacks, retail stores, auto repair shops, markets. They all sit along the dirt of the highway on either side, a wide boulevard of bustling businesses in constant motion and there is no end in sight. Everywhere cars and trucks jostle in and out of the clogged two lane highway. It seems nearly anything can be sold here from batteries to mattresses. At one point we end up in front of a truck hauling a couple of bucking horses and for a good 15 minutes are treated to equine sight of a couple of horses’ asses.

A couple of … (Photo Chip Walter)

Every now and then the road opens up a little to reveal the entrances to long swaths of land enclosed by plastic or fabric fences or thick hedges. Though it is trying to become a tourist town that caters to its beaches and sweeping dunes, San Quintín is mostly about business. It’s home to the largest agricultural company in Baja California—Los Pinos, the provider of so many of the blueberries you and I see at the grocery store. It has also become a rapidly growing center for aquaculture, and delivers millions of farmed oysters, mussels and abalones to the rest of the world. But from where we sit, the view is less than breathtaking.

An hour of traffic passes, and it’s now mid-afternoon. Finally we break out again to the open highway, and you begin to see why the Baja 1000 was a challenge for the early motorcyclists and car jockeys that first took it on. The road is never straight. It rolls up and down and banks right and left constantly, but always heads relentlessly south. There’s the occasional straight stretch, but not many. We rise into a dry plateau and rocky soil that stretches to the far horizon. Longer shadows are falling and I’m getting worried we won’t beat the setting sun to El Rosario. Images of a black night and missed turns in the desert crowd my mind.

Baja (Photo Chip Walter)

Twilight. We finally descend into a deep curve that takes us and the highway into El Rosario at last. The single hotel Dominik mentioned is closed; a victim of Covid, but luckily there is one other: Mama Espinoza’s. Its reception area sits dead on a big bend in the road, a solid stucco building with murals in bright red, yellow, tan and purple depicting coyotes, cactus, a sunset and a big emblem that reads Historic Route 56. The door is wide open, and at the other end of a dirt parking lot sits a two story stucco-built motel with eight rooms. To the right, Mama Espinoza’s Restaurant beckons our empty stomachs with the pleasing blinking sign: Abierto! Abierto!

Arriving in El Rosario at Dusk barely making the darkness deadline. (Photo Chip Walter)

We arrange to take room #2 for $48. It is spacious. There is a double bed for us and and single bed for our bags, a naked tile floor, small wrought iron glass top table and a tiny cast iron fireplace. Everything is spic and span including a very serviceable bathroom.

Even in Baja temperatures can drop into the 40s in January. I see the the stove but no wood so go back to our receptionist, a small round young lady with dark, mournful eyes and black hair to her waist. I attempt a lame investigation of how to get kindling for a fire. Complete incomprehension ensues thanks to my non-existent Spanish. We walk back to the room. When I motion the idea of creating a fire in the little stove she leaps up like she’s been shot. “No! No! No! Fuomo, fuomo!” which I took to mean we would burn the entire building to the ground if we lit up the stove. She makes a slashing gesture across her throat and runs to show me where the metal section connected to the chimney has been severed. “No, no, no!” She repeats. Fire of any kind is clearly out of the question.

But what if it gets cold? I hug my arms around my shoulders. With great solemnity she walks to the single bed behind us where heavy wool blankets lay. She picks up a bundle and says, “Aqui.” And that is that! Wool, not fire would keep us warm for the night.

We move onto dinner.

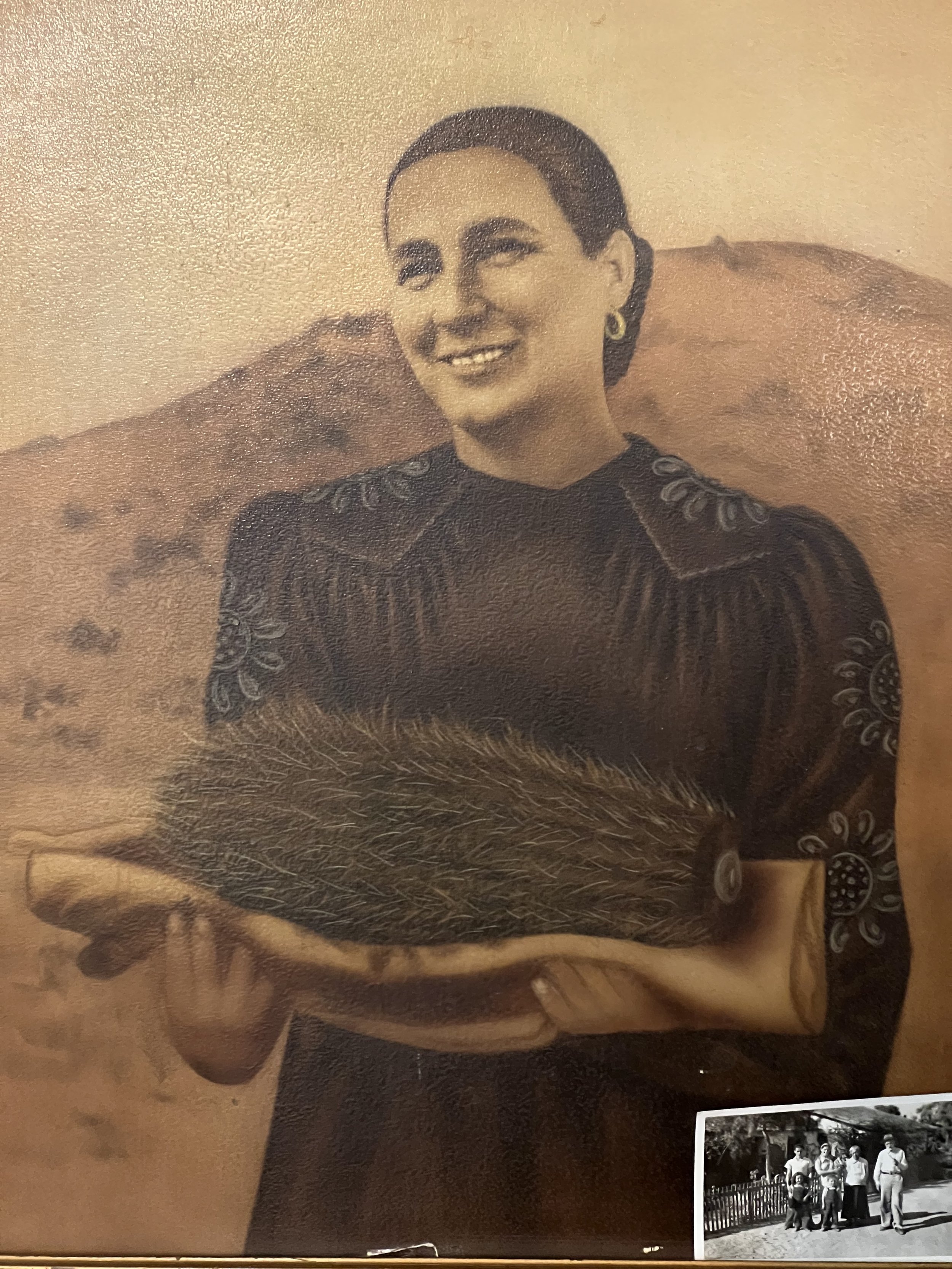

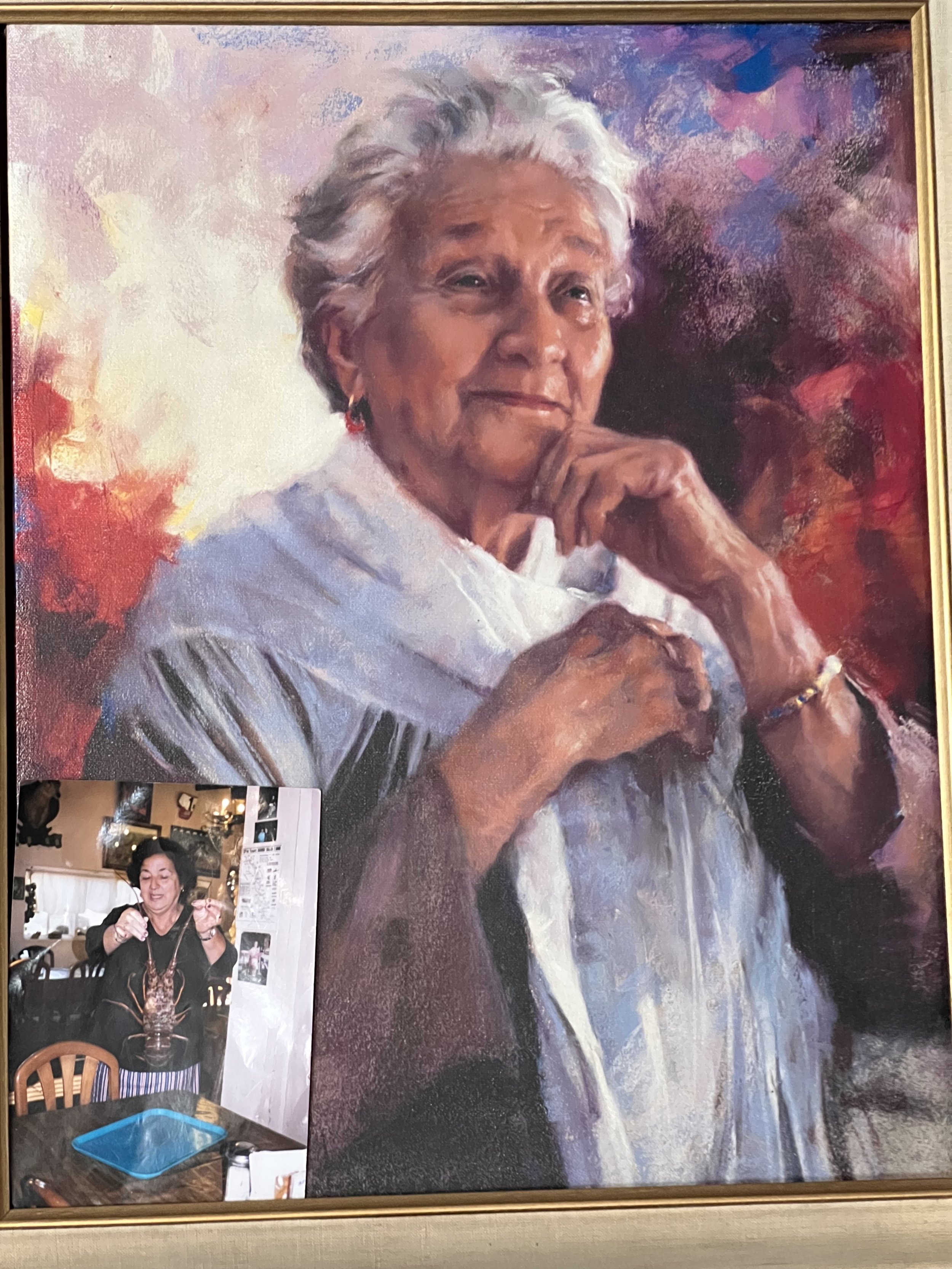

Mama Espinoza’s Restaurant is a paean to the Baja 1000; plastered head to toe with inscribed banners, pictures and posters of trucks and dune buggies and motorcycles showing off names like Jorgensen Racing, Vortex, Enduro, Larry Ragland. Brightly colored rally shirts drape themselves from the ceiling. Every kind of liquor and wine stands on shelves above the cash register. There are glass enclosed Baja 1000 t-shirts, sunglasses, Bic lighters, and a dense clustering of electronic gadgets and other Baja chachkis. Wires entangle a wifi router, but do not blot out the long, horse-leg map of the Baja 1000 route dated 2006 with the name and picture of Malcolm Smith plastered on it, apparently the winner, and a Baja legend. Among the paraphernalia, a newspaper article in English about Mama with the headline: “The Living Legend of El Rosario.” Higher up, two portraits of the legend herself hang in adoration, one the photograph of a young Mama carrying a blanket with a cactus, and the other a painting of the same handsome woman with gray hair and a wizened smile.

Mama Espinoza and the unique little Restaurant she created (Photo Chip Walter)

The Baja 1000 started in the 1960s when Jack McCormack and Walt Fulton, a couple of marketing gurus at American Honda, decided to hold a long-distance race to prove Honda’s new CL72 Scrambler could handle truly rough terrain. Bud Ekins, one of Hollywood’s premier stuntmen (he did Steve McQueen’s stunts) suggested they drive the 950 miles of rock, sand washes, dry lake beds, cattle crossings, and mountain passes from Tijuana to La Paz. March 22, 1962 his brother Dave headed off. Forty hours and 940 miles later he arrived in La Paz. Thanks to celebrities like Steve McQueen and Mario Andretti the race became one the most celebrated in the world.

In those days there were no paved roads and they certainly didn’t exist when Anita Peña started serving lobster burritos and cold drinks out of her own house to the bikers and drivers looking for sustenance as they headed south. In 1967 she built her restaurant, which was also made the first official checkpoint on the race. Ever since, she (Mama passed away several years ago) and her family have been filling the restaurant with paraphernalia, and the stomachs of patrons with very good food, including the huevos rancheros, potatoes and coffee we devoured the next morning.

The bustling metropolis of El Rosario as we depart. (Photo Chip Walter)

Guerrero Negro - Day 2 of the Baja 1000

In the dusty parking lot we get back to the Mercedes and into the desert. Rock, dust, red-dusted mountain plateaus and the occasional errant cow pass us by before we enter the heart of the Baja California Desert, a gnarled and desiccated land of immense cactus and 500 varieties of succulents. This is a mesquite/tequila paradise, and, if you don’t have a car, a great place to die from thirst or rattlesnakes. For hours we twist through the cracked and sandy land absorbing its raw beauty. At one point we pass what initially looks like a mound of pebbles, but when we arrive we find these are house and car-sized boulders heaved up in great mounds. How they got there I can’t say and so far no one else has illuminated me. (I’ll work on it.)

The Baja Desert - 30,000 Square Miles. (Photo Chip Walter)

The Baja Desert is huge; 30,000 square miles of parched earth. Half the time we travel the length of the peninsula we pass through it. We continue and in late afternoon make our next milestone: Guerrero Negro, reputed to be the largest source of salt in the world. The town’s main road is a broad concrete boulevard with sparse islands of dirt and trees. Our hotel is right on the road. The proprietor, an energetic man with a thick head of slicked back hair and nearly perfect English, reiterates the factoid about salt and then adds, “Go to the beach and you will see some of the most beautiful sunsets in the world.”

We drop our bags and take him up on his suggestion, except we aren’t entirely sure where the beach is. We drive to the end of the boulevard following the setting sun through one story retail shops and apartments and on past great salt warehouses and a maze of streets before finally finding sand, a good half mile of it. If we take the time to walk to the beach there will be no sunset to see so I snap the picture I can. The colors are spectacular, but then have you ever met a sunset you didn’t like?

The spectacular sunsets of Guerrero Negro (Photo Chip Walter)

Coming back, we search for popcorn (I have a habit), find some in a local mercado and then walk from our hotel to a fine restaurant a block away for a take away dinner of fish soup and tacos nicely wrapped up in a bag for us to engulf back in our room. Covid is still a thing.

About 3 am we are awakened by a loud argument that seems to be taking place at the base of our bed, but is in fact next door. I’m pretty sure it is our proprietor and his wife having it out, but my Spanish eludes me again and I can’t fathom what the ruckus is all about. Finally we fall back asleep, even if the angry couple doesn’t.

The next morning, showered, but somewhat sleep deprived, we find coffee at a local cafe, and return to pack up. As we pull away from the hotel, I glance back to the scene of the crime. Dead quiet in the building next to ours. Peace at last? Or did someone get axed?

We rev up the Mercedes, refill its tank and return to Route 1 which takes us south before arcing southeast across the great peninsula to the Sea of Cortez and our next destination, Mulége. Or at least that’s what we thought…

More to come.

Your vagabonds … cracking on!

C-Squared

This story through Baja continues in Driving the Baja 1000 - Part Two

This is a series about a Vagabond’s Adventures - author and National Geographic Explorer Chip Walter and his wife Cyndy’s effort to capture their experience exploring all seven continents, all seven seas and 100+ countries, never traveling by jet.

A Note to our readers…

Dispatch XXIV is the first newsletter that does not immediately follow the last location we visited. (Dispatch XXIII - Monument Valley). This one skips forward to Mexico and begins our drive down the length of Baja, one thousand miles. We did that February 2022. If you want to check and see what we did in between those those two locations, Polarsteps fills them all in at the interactive world map or visit Polarsteps on your phone, iPad or computer here.

——————————————————————————————————————

As of this Dispatch …

We have travelled 9,000 miles, across four ferries, on eight trains, visiting four World Heritage Sites, through 21 states, 13 National Parks and monuments and three countries, in 45 different beds, and run through more keys than a grand piano.