Spirits, Devils and Wyoming

Dispatch XIX

A Vagabond’s Adventure

Continent # 1: North America

Heading South to Wyoming

Day 57 - November 20-23, 2021

The sky was big in Montana, just as its license plates say it should be as we skirted its western border and headed south to Wyoming. We rolled along a secondary highway past ranches and seas of grass waving in the crisp November air. Its was relaxing. Hours passed and the sun had set when we made it to the little town of Huelet. The hotel lobby was festooned with the heads of magnificent elk, bison and deer now no longer with us that ran up and around the big staircase that led to our room.

A Few Locals No Longer With Us in Huelet, Wyoming

At the desk there was a message for the clients in front of a box of old white towels. It read:

HUNTERS

“These rags are here for you to use,

To clean your guns if you chose!

They’re also good to wipe up mud,

Blood and guts and all that crud!

AND

If your boots are full of sludge,

Turn the big rags into rugs!!

So keep your maid’s head from spinning’,

PLEASE don’t use your bathroom linens!”

THANK YOU! THE BEST WESTERN DEVIL’S TOWER INN

We had a good laugh over that and so did the two hunters who made their way upstairs wearing head-to-toe camouflage. We followed behind, unloaded our bags and made our way to the tiny town’s main street, no more than 75 yards from one end to the other. The Ponderosa was the place for dinner the receptionist said, and we found it, all wooden slats with a low shingled roof. A pot-bellied stove sat like an old friend inside, and at the far end was a bar no longer than the length of an upended door. Tables were crammed cheek-by-jowl across two rooms filled to capacity with people who did not look like me and Cyn. We were not suited up in hunting gear; no big boots, or camo hats, or thick brown canvas pants. We stood out like tarantulas on a birthday cake.

A large woman with much hair was all business as she seated us at the one available table, hands on her ample hips. She was busy woman and had no time for nonsense, but we did learn that this was the beginning of hunting season thus the packed house and message at the Best Western.

“What do you recommend?” I asked.

She rattled off the Ponderosa’s main meals, but said the special was meatloaf. “It’s really good. Cook makes it with a combination of elk, deer, bison and beef.”

I wondered if they might be related to the fellers on the Best Western walls.

“Comes with a salad,” the waitress added, warming up a little. (Cyndy’s smile has that effect on people.) “The soup’s good too,”

“What’s the soup?”

“Tomato bisque.”

We didn’t see that coming.

“We’ll have that, and the meatloaf, please!”

In no time, plates with two enormous slabs of ground meat arrived laden with thick brown gravy, mashed potatoes, an excellent salad and the best tomato bisque I’ve ever had.

We ate and absorbed the room. I could feel a low level the energy. Nothing loud or overbearing, no big drinkers or laughers barking out bad jokes, just a kind of buzz created by the aggregated conversations, men mostly, some with their boys at the table, expectant, excited about what the next day might bring.

In the morning we explored Huelet, what there was of it. It was cool and the bright, and not a soul to be found. A few clapboard businesses on either side of the Ponderosa sat forlornly along main street. They showed off new signage designed to look authentically old, the better to attract patrons who yearned for the days of the great Wild West. But nearly everything was closed. COVID had been unkind to the town, and it was not the high season, unless you were a hunter.

Main Street Huelet, Wy. (Photo-Chip Walter)

We drove out of town and headed along what local marketers like to call the Spirit Highway. It runs along the Belle Forche River to places like the Vore Buffalo Hump and the 120-year-old General Store in Aladdin. Or you could visit Huelet, and watch the rodeo, as long as it was the right time of year. The idea of the Sprit Highway was to get some mainstream tourists to show up in the boondocks. It reminded me of Doane Robinson coming up with the idea for Mount Rushmore. Anything to bring in the hoards because these small towns everywhere in the United States (and later, we realized, throughout the world) are dying. Life is too simple for the town’s children nowadays, their heads being filled with Netflix and HBO, video games and the vast knowledge available right there in the hands of their smart phones. They wanted more than harsh winters and sputtering economies. But if people could only see what the Spirit Highway had to offer, a piece of the past that is only appreciated at a certain age, a realization that roots and history are important. If only they could see, then surely they could bring in millions, and the restaurants and small museums and rodeos, music and native festivals would blossom like spring flowers on the prairie. It occurred to me that what they really wanted was Medora, a former backwater that now brings in hundreds of thousands of cash paying tourists. But Huelet was a long way from anything like that, and I feared it might never make it to the land of Medora. On the other hand, there is Devils Tower, the place we had come to see.

The Tower

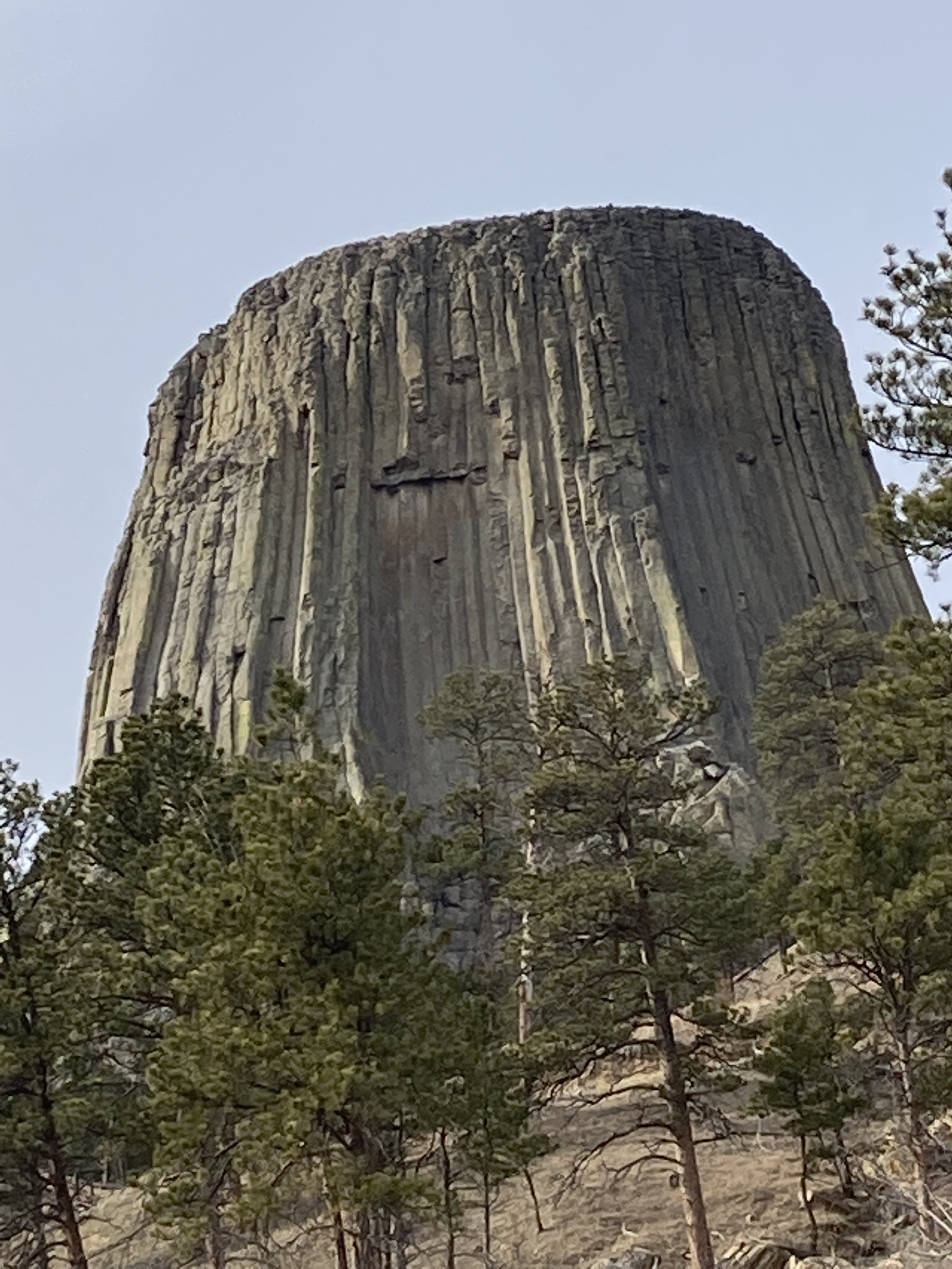

Devils Tower gives new meaning to the word “there.” Because if anything is “there” it is that massive crag; planted, enormous out of all proportion to its surroundings, solitary and forbidding; a remarkable piece of igneous rock that has refused to be flattened by wind, water, earthquakes or blizzards.

The Bear’s Lair (Photo - Chip Walter)

It is a sacred place to Native Americans who have spent thousands of years in the company of the great edifice. I could see why. In this flat land it rises 867 feet from summit to base, godlike, and when I saw it from afar, I had the impression that it might shake itself free and begin to walk in search of others of its kind. Cyn and I stopped the car, and stared.

The name Devils Tower is a mistake, it turns out, made by an interpreter who somehow read a Native American’s description of the place as “Bad God’s Tower.” That name was then revamped into Devi’s Tower, and, despite some debate, it has remained unchanged since 1875.

The Cheyenne, Lakota, Crow and Kiowa have all given the rock a variety of other names that long predate Devil’s Tower: Bear’s Lodge, Bear Lair, Home of Bears, Tree Rock and Brown Buffalo Horn. The bear references come from several myths, but my favorite is the Kiowa and Lakota version. A group of girls are playing when several giant bears spot them and give chase. The girls scramble to the top of the rock, fall to their knees and pray to the Great Spirit certain they will die. Suddenly, their prayers are answered when the rock mounts toward the heavens. Still the bears (or in some tellings a single huge bear) continue to claw their way up the rock, scraping the deep ridges that give the tower its unsettling and eccentric features. Eventually the girls reach the sky, and there turn magically into the stars of the Pleiades.

If anyone knows about the Tower, it’s probably because of Steven Spielberg’s blockbuster 1977 movie Close Encounters of the Third Kind. (See Drew Moniot’s excellent companion piece in our library: “Remembering Close Encounters.”) Like Native Americans, Spielberg understood the mythic power of the place, a thing that the movie’s main characters couldn’t get out of their heads; so powerful it drew them to it as if magnetized. I could see that, now that I stood there in front of the thing.

The structure impressed Theodore Roosevelt enough that he made it the nation’s first national monument in 1906.

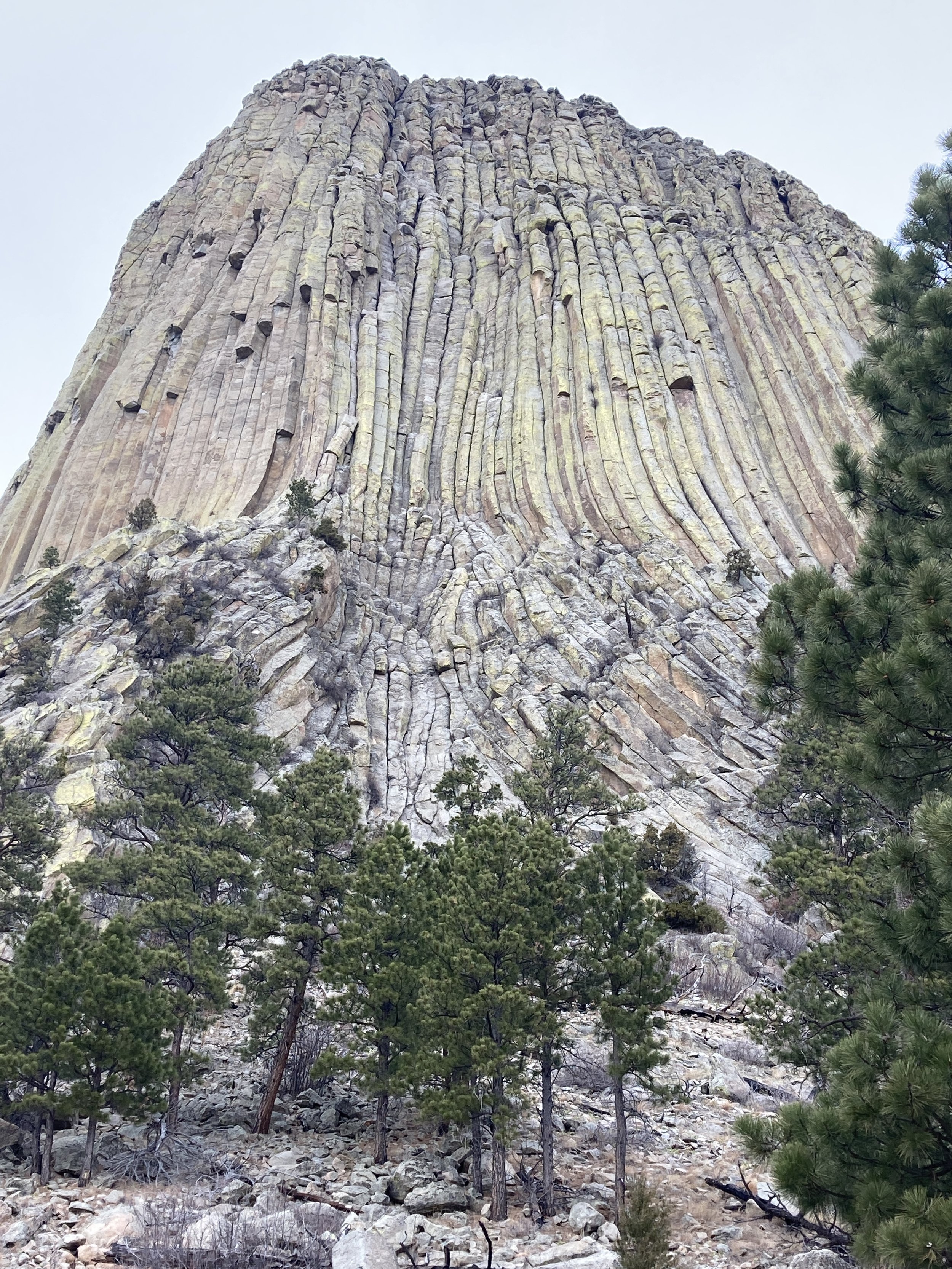

A Closer View of the Tower (Photo - Chip Walter)

Cyndy and I thought we might be forced to deal with long lines when we drove to the entrance, but in November there were no clogged parking lots. We wandered through the tall pine woods and met maybe six people as we made a circuit around the mountain. Flagging wisps of clothing and ribbons hung on certain tree limbs, each representing a wish or a prayer for a loved one, a personal bit of someone’s soul, adrift and flying in a sacred place.

Personal Bits of Someone’s Soul (Photos-Chip Walter)

Every view of the tower gave you a different look, but every look was marvelous. All around we walked over or beside rocks the size of cars and houses that time and erosion had toppled from the pillars of molten rock that geologist believe formed the long, razory lines that rake the edifice from top to base.

Scientists can’t truly say how a piece of rock this magnificent came to be, but the general theory is that the collision that formed the Rocky Mountains 60 million years ago created a crucible that drove molten lava into a chamber of sorts, and as the column cooled it developed its phallic ridges. Later an ancient version of the Belle Forche River carved the land around it away leaving its lacerated look behind.

Every view is marvelous. (Photo - Chip Walter)

Wheatland

Once we had stamped the “passport” the National Park Service provides as proof that we have visited certain landmarks, we steered our car into Wyoming directly south. We rolled away from the Belle Forche and into another ocean of grass. Flat wasn’t a good enough description for what we drove through. I felt we needed bigger, better words. To someone like me, it’s strange to pass into such a place. I grew up in the hills and valleys of western Pennsylvania where flatness was unknown, and horizons were always jagged or humped. We through town after small town with populations of 100, sometimes maybe a thousand, but that would have been an aberration. More cows than humans live in Wyoming (twice as many to be precise). No matter which town we passed through, each had a broad main street wide enough for five lanes if anyone needed them. I wondered why they were so broad. In some larger towns, the roads begin to criss cross into a small grid, their low buildings sprawling in all directions. They do this, I supposed, because they can. There is no shortage of space in Wyoming.

Each town, of course, has its own personality. Sturgis (rowdy) is not Hill City or Keystone (somnolent in winter, family-like in summer) nor again anything like Deadwood or Huelet or Morecroft, Custer or Wheatland, our next destination. we were headed there for no other reason than it seemed a reasonable distance to cover on our way to Colorado.

Wheatland struck me as a town where money and jobs were in short supply. COVID had undoubtedly done dame here as well as everywhere else, but even in better times, the buildings and streets showed signs of struggle. At the turn of the 20th century, not a single road connected Wheatland to the rest of the world and if anyone came to town it was by rail. These days it was home to the Wheatland Irrigator football team and Dick Cheney, ex vice-president to George W. Bush.

Cyn and I found a hotel and the next day wandered some of the poorer parts of town. In one battered home a window was draped with a confederate flag. Outside another house, a dusty lawn with a sign read, “God, guts and glory.” And across the Post Office the side of a garage was filled with a wall-sized image of a cowboy busting a bronco, hat raised, delighted and defiant.

Along Gilcrist Street, the town’s main drag, we saw some signs of life: a small grocery and bank and several single-story buildings, mostly brick. At 875 Gilcrest The Wandering Hermit found us, an excellent bookstore founded by Dan Brecht and his son Zack that would have done any city proud. Long stacks of books lined the aisles, many devoted to the history of the west. There were thoughtful gifts, cards and journals and a beautiful coffee bar of polished oak. The building had changed it’s face and purpose many times since it was built in 1903: at first a hardware store, later a secondhand shop and a Christian bookstore, then at various times a place where you could buy stuffed but quite dead animals, antiques, western-wear, plumbing goods, and Straw’s and Thorne’s Drugs. Dan was committed to restoring the best of the old building and it showed in the polished wood floors, high ceilinged tin roof and the 1920s era lighting fixtures that illuminated the stacks below. Zach’s passion was obvious and they were making it work. It was a testament to the love of books, and the town.

In the low afternoon light the evening before we headed out of town, we witnessed something remarkable. Far off beyond the prairie, at the base of the Rocky Mountains, stood an enormous cloud and below it rain poured out of the sky as if a spigot had been turned on. It seemed a statement to me direct from Wyoming: “Here, see what I can do! See what is possible to see in this vastness! A place so large that whole weather systems can stun you like the sudden appearance of an immense and feral animal.” We and others stood in a parking lot gawking. What a show. And then we ate some good Mexican food and headed back to our hotel.

Here, see what I can do! (Photo - Chip Walter)

The next morning we departed again, this time to Denver and then onto Jackson Hole for a Thanksgiving dinner with two of our daughters and their beaux. The next stop after that was Denver where we would board AmTrak’s California Zephyr to ply our way over the Rockies and into Grand Junction to follow the Colorado River to Moab, Utah.

This is a series about a Vagabond’s Adventures - author and National Geographic Explorer Chip Walter and his wife Cyndy’s personal journey to explore all seven continents, all seven seas and 100+ countries, never traveling by jet.

As of this Dispatch …

We have travelled 5417 miles, across four ferries, on five trains, visiting three World Heritage Sites, through 15 states, five National Parks and memorials, one National Historical Landmark, and three Canadian provinces, in 31 different beds, and run through more pens than Ernest Hemingway.